From Question to Judgment

Why Assessments Alone Are Insufficient for Force-Based Decision Making

In rope rescue, failure rarely occurs because a team lacked equipment or memorized procedures incorrectly. It occurs because a system was repurposed without re-evaluating how forces now behave.

This is where most training subtly breaks down.

Assessment questions are excellent at confirming whether a rescuer recognizes a known hazard. They are far less effective at revealing whether that rescuer understands how a system’s risk profile changes when force direction, magnitude, or geometry changes.

Critical analysis exists to close that gap.

This article examines how a single assessment question—focused on anchor behavior under changing force direction—can serve as the entry point into deeper system-level reasoning. More importantly, it explains why assessment and critical analysis must remain distinct but deliberately connected if we expect technicians to make sound decisions in non-textbook environments.

The Assessment Function: Identifying the New Dominant Failure Mode

Consider the scenario:

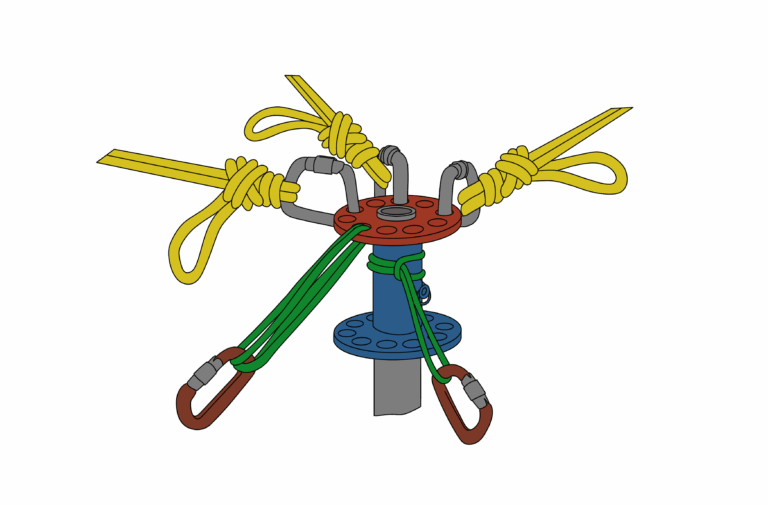

A massive, well-seated boulder is selected as a “bombproof” anchor for a vertical descent. Later, the same anchor is repurposed for a high-tension horizontal system applying lateral force.

At the assessment level, the question is simple and intentionally narrow:

What new failure mode becomes the primary concern?

The correct answer identifies that lateral force introduces the risk of sliding or rolling, where friction and gravitational seating may be overcome.

This question does not ask the learner to calculate force vectors, evaluate coefficients of friction, or analyze subsurface geology. That omission is intentional.

An assessment is doing one job only:

-

Verifying that the learner understands anchors are force-direction dependent systems, not static objects.

If the learner cannot recognize that a laterally loaded anchor behaves differently than a vertically loaded one, they are not ready for deeper analysis. The assessment acts as a gate, not a destination.

Where Assessment Ends — and Why It Must

A common instructional mistake is assuming that a correct answer implies understanding.

It does not.

The assessment confirms recognition of the dominant risk, but it tells us nothing about whether the learner understands:

-

Why gravity stabilized the anchor in one configuration

-

Why friction becomes a limiting factor in another

-

How increasing line tension compounds instability

-

Or what secondary failures now become more likely (edge abrasion, anchor migration, load amplification)

This is where critical analysis begins.

Critical Analysis: Reconstructing the System Under New Forces

Critical analysis reframes the same scenario, but with a different expectation:

Instead of asking what is the failure mode?, it asks:

-

What changed in the force environment?

-

Which stabilizing mechanisms were lost or reversed?

-

What assumptions were valid before but are invalid now?

The boulder itself has not changed.

The system has.

Under vertical loading, gravity increases normal force, enhancing friction and seating the anchor. Under lateral loading, gravity no longer contributes to stability in the same way; instead, it becomes a passive factor while horizontal force attempts to translate or rotate the anchor.

Critical analysis forces the learner to articulate that shift explicitly.

This is not academic. In real rescues, anchors are repurposed constantly—sometimes out of necessity, sometimes out of convenience. Without system-level reasoning, “bombproof” becomes a misleading label rather than a conditional judgment.

Why the Bridge Matters in Real Operations

If assessment and critical analysis are not intentionally linked, two failure patterns emerge:

-

Assessment-only training produces technicians who can identify textbook hazards but struggle when systems are reconfigured.

-

Analysis-only training produces discussions without anchors to reality, where reasoning floats without verification.

The bridge is not optional.

-

Assessment verifies recognition

-

Critical analysis develops judgment

-

Judgment governs decision-making under uncertainty

The same system should appear in both contexts, but the questions must change.

Assessment asks:

“What is the dominant risk?”

Critical analysis asks:

“Why did the dominant risk change, and what does that imply for the rest of the system?”

Summary

Assessments and critical analysis are not interchangeable tools. They serve different cognitive functions, and when used correctly, they reinforce each other.

An assessment confirms that a rescuer recognizes how force direction alters anchor behavior. Critical analysis ensures that rescuer understands why that alteration matters, how it propagates through the system, and when previously safe assumptions no longer apply.

In technical rescue, systems rarely fail because a team chose the wrong answer.

They fail because the answer was treated as sufficient reasoning.

Bridging assessment to critical analysis is how training moves from correctness to competence—and from competence to judgment.

Peace on your Days

Lance