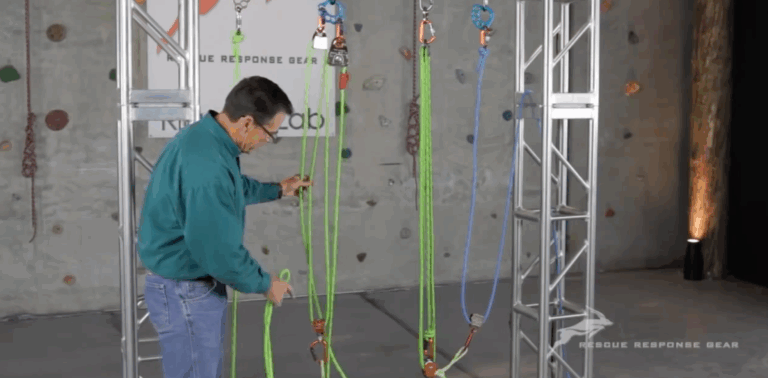

Mechanical advantage lies at the heart of rope rescue, and pulleys are the tools that make it possible. By redirecting force and multiplying effort, pulley systems enable rescuers to move loads that would otherwise be unmanageable. Understanding how these systems work—specifically how rope anchoring, pulley placement, and rope routing affect efficiency—is essential for building safe, predictable, and efficient haul setups.

This lesson explores the five essential rules of pulley systems, explaining how each principle shapes the mechanical advantage achieved and how small design decisions determine whether a system works efficiently or wastes energy.

The Role of Pulleys in Mechanical Advantage

At its simplest, a pulley changes the direction of force. When combined in a system, pulleys divide the load among rope segments, multiplying the force that can be applied. The goal is not just to lift more weight, but to do so safely, efficiently, and with control.

Every pulley added to a system increases its potential efficiency—but only if configured correctly. The placement of anchors, the path of the rope, and whether the rope end is attached to the anchor or the load all define the ratio of mechanical advantage.

To visualize the relationship, think of pulleys as multipliers of opportunity: each segment of rope between pulleys carries a portion of the load, spreading the effort and improving control.

Rule One – If the Rope is Anchored, the Mechanical Advantage is Even

When the rope’s fixed end is attached to an anchor, the resulting system produces an even-numbered mechanical advantage. For instance, a 2:1 or 4:1 system begins at the anchor because the first pulley redirects force back toward the load.

In this setup, each rope segment between pulleys shares the tension evenly, effectively halving the effort needed to move the load. Because the anchor is the fixed point of reference, the pulling direction is opposite to the load’s movement.

Even-numbered systems are common for controlled hauls where the rescuer works opposite the load path—such as raising a litter from below an edge or tensioning a horizontal line.

Rule Two – If the Rope is Tied at the Load, the Mechanical Advantage is Odd

When the rope is tied directly to the load, the resulting system becomes an odd-numbered mechanical advantage—such as 3:1 or 5:1.

Here, the rope’s input starts at the load and passes through pulleys on the anchor or intermediate points before returning toward the rescuer. Because the rope moves with the load, the number of tensioned segments pulling on the load is odd.

This configuration allows the rescuer to pull in the same direction as the load’s travel. Odd-numbered systems are frequently used for direct pull hauls, where space is limited or when the operator’s position must align with the direction of movement, such as in confined-space or vertical extraction operations.

Rule Three – The Last Pulley at the Anchor Changes Direction

In any pulley system, the final pulley at the anchor determines the direction in which the rescuer pulls. If this pulley is added to redirect the rope, it does not change the system’s mechanical advantage; it merely changes the direction of pull for convenience or safety.

This directional pulley allows the haul team to stand in a safer or more ergonomic position, keeping the rope away from edges, obstacles, or potential pinch points. Understanding this distinction is critical: a redirection pulley does not increase force multiplication—it simply makes the work more manageable and controlled.

Rule Four – Counting Pulleys and Adding One Reveals the Mechanical Advantage

A simple way to calculate mechanical advantage is to count the number of rope segments supporting the load and add one if the rope end is being pulled by hand. This visual rule provides a quick field reference for determining system efficiency without complex equations.

For example:

-

A pulley attached to the load with one redirect at the anchor yields a 2:1 system.

-

Two pulleys—one on the load and one on the anchor—produce a 3:1 system.

-

Add another moving pulley, and you have a 4:1 or greater compound setup.

While real systems must account for friction losses, this counting method helps teams estimate expected performance and select appropriate anchor strength and haul team size.

Rule Five – Combining Simple Systems Creates Compounding Effects

The final rule recognizes that mechanical advantage can be compounded by attaching one simple system to another. For example, pulling on a 3:1 system that is itself connected to a 2:1 setup creates a compound 6:1 mechanical advantage.

However, compounding comes with trade-offs: every added pulley increases rope length and friction. The more rope required to move the load, the slower the system becomes. This relationship highlights the balance between power and distance—greater advantage means greater rope travel and more resets.

In practice, rescuers must evaluate whether the additional mechanical gain justifies the complexity and friction introduced. Often, a well-optimized simple system performs better than an overbuilt compound one.

Applied Understanding in Rigging Systems

The five rules are more than theoretical—they define how every haul, tension, and progress capture system behaves in the field.

In an operational context:

-

A 2:1 is ideal for short lifts or pre-tensioning anchors.

-

A 3:1 offers versatility and manageable pulling distance for standard rescues.

-

A 5:1 or compound system may be used when lifting a heavy litter or overcoming long vertical distances.

Recognizing these ratios allows teams to calculate effort, anticipate rope travel, and understand the system’s mechanical behavior under load.

Moreover, the ability to visually diagnose a system—knowing instantly whether it’s even, odd, or directional—builds confidence and predictability in high-stress situations.

Efficiency and Friction Considerations

Real-world performance seldom matches theoretical values because friction reduces mechanical efficiency. Each pulley introduces minor losses through bearing resistance and rope flex. As a result, a theoretical 3:1 may perform closer to a 2.6:1 depending on equipment condition and load.

Minimizing friction by using high-efficiency pulleys and maintaining proper rope alignment ensures that the system behaves predictably. The practical takeaway is simple: mechanical advantage exists only when the system moves freely.

Summary

Understanding pulley systems means understanding how geometry and rope routing convert motion into mechanical advantage. Whether anchored at the load or the anchor, every pulley affects force distribution and pulling direction.

The five rules—anchored systems are even, load-tied systems are odd, the last pulley redirects, counting reveals ratio, and compounding multiplies effect—provide a clear framework for analyzing any mechanical setup in the field.

Mastering these principles allows rescuers to move efficiently from theory to reality, transforming complex pulley networks into simple, predictable tools of controlled force.

Peace on your Days

Lance