Safety in rope rescue is not the presence of a checklist or a perfect system on paper—it is a discipline woven into every decision a team makes. Skill alone does not guarantee safety, nor does good equipment. What guarantees safety is a mindset: the deliberate, consistent evaluation of risk, the disciplined use of redundancy, and the commitment to checking systems even when you think you already know they’re right. Rope rescue safety is the unifying thread between knowledge, equipment, terrain, and human behavior. When teams understand this, they move from merely completing evolutions to executing true professional rescue operations.

Safety is not an accessory to rope work. It is the rope work. Every anchor, every belay, every approach to the edge, every piece of communication either increases or decreases exposure. The goal is simple: move rescuers and subjects through a high-risk environment while minimizing the chance of failure. This requires habits, judgment, and systems that work reliably even when stress is high or conditions degrade.

Understanding Risk in Rope Rescue

Every rope rescue operation contains inherent risk. The terrain is unforgiving, the systems are under load, and the consequences of failure can be severe. While we never eliminate risk, we minimize it through thoughtful preparation and deliberate system design. Most failures do not come from surprises—they come from known weak points that were ignored or misunderstood.

The first step in managing risk is understanding its sources. Rope rescue presents multiple layers of exposure, and teams must recognize how and where each one can appear.

Core categories of risk include:

• System failure – anchors, components, rope condition, tensile strength, knots, edge interaction

• Human failure – insufficient training, height intolerance, poor decision-making, inexperience

• Communication failure – unclear plans, overlapping commands, multi-agency confusion

Each factor must be evaluated before a system is built, while it is under load, and again once the team transitions between phases of the rescue. This long-view approach keeps teams from blindly trusting gear or procedures that may no longer be appropriate.

NFPA 1670 and NFPA 1006 provide a standardized framework for identifying risk, competency levels, and operational expectations. These standards serve as a starting point for safe operations—not a complete solution. Teams must tailor these principles to their own terrain, personnel, and operational realities.

Redundancy and the Concept of Backup Systems

Redundancy is one of the defining principles of rope rescue safety. Every system is backed up by another system. Every anchor is supported by another anchor. Every mainline is paired with a belay. This double-rope or two-rope methodology recognizes the reality that things fail. Rope wears, anchors, move, edge protection shifts, and humans make mistakes.

Redundancy is the engineered answer to those uncertainties.

Every rescuer should regularly ask:

“If this part of the system fails, what will catch me?”

But redundancy must be applied intelligently. Overbuilding a system slows operations and can create new hazards. An overly complex system increases the load on the litter tender, introduces confusion during transitions, and may compromise patient care. Safety comes from balance—using enough backup to manage risk without creating unnecessary complications.

Key factors when deciding how much redundancy to build:

• Likelihood of component failure

• Environmental hazards (wet rock, unstable edges, cold conditions)

• Available staffing and experience level

• Practicality of additional backups

• Awareness of unavoidable weak links

Redundancy is not a competition to build the most complex rigging. It is the disciplined application of backups where they matter most.

Belays and Their Role in System Safety

If the primary support system fails, someone must remain secure. That is the purpose of the belay. Belays are not optional—they are fundamental to rope rescue safety in most environments. A failure may occur due to poor terrain, compromised anchors, rope degradation, or a mistake under stress. The belay exists to absorb the consequences.

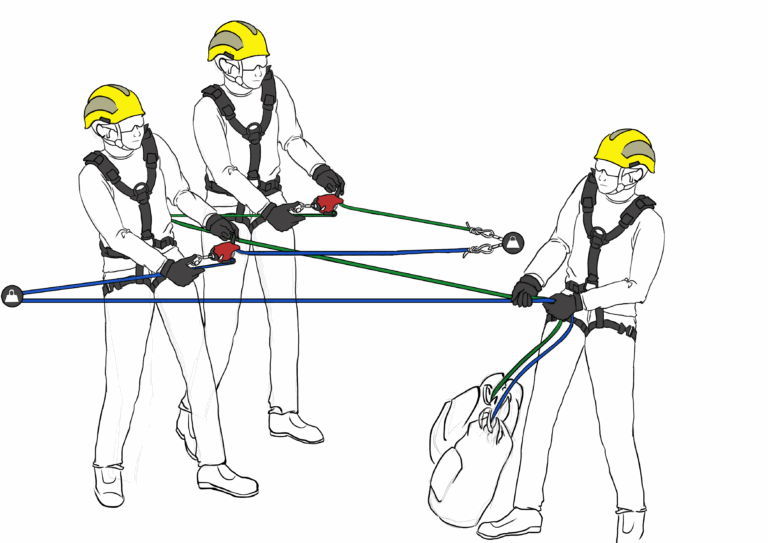

In modern Twin Tension Rope Systems (TTRS), both lines share the load, meaning each must be capable of supporting the total weight independently. This design spreads forces more evenly, reduces shock if a line fails, and simplifies transitions.

Belays are equally important during training. Many new students experience significant anxiety during early rappels. A properly managed belay protects them physically and allows them to focus on technique rather than fear. Training belayers also strengthens the team’s capability, ensuring that everyone understands both sides of the rope.

Belay considerations include:

• Ability to support full system load

• Dynamic forces during failure events

• Terrain that may compromise rope travel

• Belayer proficiency and focus

Belays protect students, rescuers, and subjects—and are integral to professional rope operations.

Single Rope Technique (SRT) — The Exception

Single Rope Technique exists because certain environments make belays impractical. Cavers discovered long ago that belay lines would snag, lock, or stop progress on long, complex descents. To solve this, they developed SRT systems that intentionally eliminate the belay to maintain mobility and efficiency.

SRT demands higher precision and greater care than double-rope systems. Without a belay, there is no margin for error. Only teams with the skill, judgment, and physical capability to manage a single-line environment should employ it.

Safety considerations for SRT:

• Use the highest-quality rope available—this is your only line

• Edge protection becomes absolutely mandatory

• Maintain two points of contact during transitions

• Treat the connection between you and the rope as your “self-bela.”

Judgment is essential. Not all environments support SRT, and not all teams are prepared for it.

Safety Checks: The Habit That Prevents Accidents

The fastest way to reduce risk is also the simplest: check the system. A safety check takes seconds and can prevent catastrophic failure. Complacency, fatigue, and overconfidence are the most common reasons safety checks are skipped—and they’re also the most common contributors to accidents.

Safety checks must be performed on your own rigging and on the rigging of others. A different set of eyes sees different things. Teams that formalize safety checks move faster, not slower, because errors are caught early.

Two validated checking methods are commonly used:

Safety Check

• A partner or designated safety officer inspects the rigging

• Confirms correct connections, knots, and direction of travel

• Should be performed at setup and after any system modification

Touch System

• Physically touch each component of the system

• Ensures the rescuer does not skip over visual blind spots

• If you cannot touch it, point to it

Rope rescue systems wear over time. Training evolutions add stress and friction. Safety checks are essential before every evolution.

Safety During Training

Training environments carry unique risks. New rescuers may be unfamiliar with equipment, uncomfortable at height, or overwhelmed by the pace of instruction. Fear is normal—height amplifies everything. A fearful rescuer is more prone to mistakes and may misjudge their system or overlook key steps.

Managing fear begins with confidence-building. New rescuers should start with short, controlled rappels, where instructors can support them physically and psychologically. As confidence grows, complexity and height can be added.

Training considerations include:

• Evaluate team members’ comfort with height

• Assign low-angle positions to those who cannot work exposed

• Use progressive exposure to build trust and technique

Fear is not a flaw—it is a natural response. The goal is to replace fear with trust in equipment, training, and team.

Strengths and Weak Links

A rope rescue system is only as strong as its weakest link. Ropes lose strength with age. Knots significantly reduce tensile capacity. Contact points alter rope behavior. System placement on edges and hardware changes how forces are distributed.

Understanding system strength requires ongoing evaluation.

Key components affecting system strength:

• New vs. aged tensile strength

• Knot efficiency and placement

• Edge friction and protection

• Anchor geometry and loading angles

• Wear from repeated use

Judgment is required. Teams must recognize which components are subject to stress and which ones must be reinforced or retired.

Live Load vs Simulated Load Training

There is an ongoing debate about whether teams should train with manikins or live patients. Both approaches have value, and both carry risk.

A manikin reduces exposure during complex terrain transitions or difficult rigging scenarios. It protects students who may not yet have the proficiency to manage a real person safely.

Live-load training, however, offers realism that no manikin can replicate.

Advantages of live-load training include:

• Feedback from the patient’s perspective

• Greater awareness of smoothness and comfort

• More realistic movement and positioning

• Stronger team communication

Live loads are especially useful when evaluating how teams handle patient movement into position, loading transitions, and tight-terrain access. Still, teams must carefully evaluate whether conditions justify a live load. If a scenario is too dangerous for a patient, it is probably too dangerous for a tender as well.

Multi-Agency Safety Considerations

Safety becomes more complex when multiple agencies are involved. Different command cultures, varying skill levels, and unfamiliar equipment create new opportunities for confusion. Teams must approach multi-agency operations with professionalism, clarity, and tact.

Your team leader remains responsible for the safety of your personnel—even if another agency leads the incident. If conditions do not meet your team’s standard of safety, the team leader may need to decline participation. While difficult, this decision protects both the team and the subject.

Key steps in multi-agency safety:

• Identify the incident commander immediately

• Clarify your team’s responsibilities

• Determine medical control and patient-care authority

• Evaluate existing systems and anchors

• Stabilize the subject and establish belays

• Integrate tactfully with the existing teams

Effective communication is your most important safety tool. Intelligent questions and clear briefings help establish trust and ensure that teams work together efficiently.

No agency will have the same level of rope expertise. Your professionalism becomes the connector between teams, allowing you to merge seamlessly into ongoing operations and elevate scene safety.

Rope Rescue Safety Is the Unwritten Contract of Professional Teams

Safety is not a single decision, but thousands of small choices made consistently across every evolution. It is redundancy applied intelligently. It is belays managed with discipline. It is understanding fear, performing checks, evaluating system strength, and communicating clearly with other agencies. Safety is the true measure of professionalism in rope rescue.

The teams that excel are those who treat safety not as an afterthought, but as their guiding principle. When every member understands that safety is their personal responsibility—not the job of one designated person—rope rescue becomes what it is meant to be: controlled, predictable, and capable of protecting both rescuer and subject under the most difficult conditions.

Peace on your Days

Lance