High Angle Heroes Navigating the Complexities of Antenna Tower and Caged Ladder Rescue

The modern skyline is dotted with structures that reach hundreds—sometimes thousands—of feet into the air: antenna towers, wind turbines, power transmission poles, and industrial caged ladders. As critical as they are to communications and infrastructure, they present one of the most formidable challenges in rescue operations. When things go wrong up there, access is narrow, movement is limited, and the margin for error vanishes.

This blog walks through the layered complexity of rescues in these vertical environments, from ground-up rigging and climbing protection to high-angle lowering techniques. When rope rescue teams face steel, wind, and gravity all at once, every step—from system setup to knot passing—is an exercise in calculated precision.

Why These Environments Demand More

High-angle structural rescues differ fundamentally from typical rope rescue scenarios. The verticality is extreme, the environment unforgiving, and the workspace cramped or obstructed.

Key Operational Factors Include:

-

Significant Height: Operations can extend well beyond 150 feet, with some rescues surpassing 1,000 feet. This requires multi-pitch rope systems and careful rigging logistics.

-

Environmental Exposure: Rescuers are exposed to wind, sun, cold, and other high-altitude risks while suspended.

-

Minimal Work Space: Platforms are tight. Caged ladders offer little room for gear management or patient handling.

-

Structural Hazards: Cross-members, antenna arrays, guy wires, and cables present snag points and sharp edges that can damage ropes and impede movement.

-

Subject Condition: The person in distress may be unconscious, injured, or unable to assist in their own rescue, complicating both time and method.

Phase 1: From Ground to Subject – Rigging with Intent

A successful rescue begins on the ground—literally. Pre-planning, scene sizing, and ground-based rigging determine whether the team can even reach the subject safely.

Rescuers first identify the location and condition of the subject and establish the best position for a ground anchor. The first ascending technician—equipped with a harness, tools, and a radio—carries a lightweight drop line (typically 8–9mm), which acts as the lifeline to deliver heavier rescue gear once they’ve reached the subject.

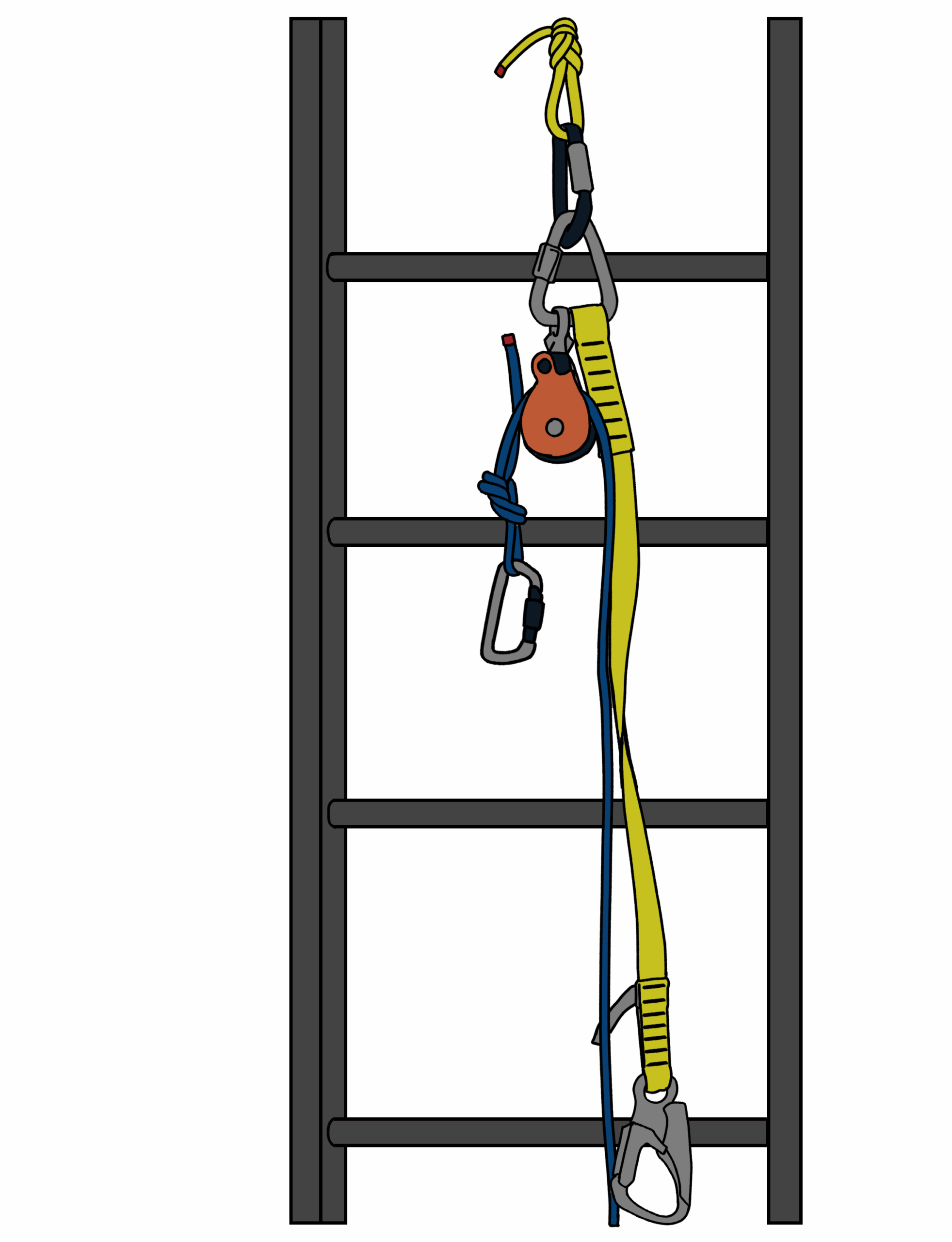

To ensure fall protection during ascent, rescuers rely on a bypass lanyard. This twin-leg lanyard allows continuous protection, even while transitioning past rungs, obstructions, or anchor points. In more complex or medical scenarios, a second rescuer may ascend to assist with patient care or harness transfer.

Phase 2: Rigging at Height – Anchors, Pulleys, and Precision

Once at the subject’s location, rigging becomes a technical dance of control, communication, and clearances.

-

System Delivery: The drop line is used to haul up the main rescue and belay lines.

-

Change-of-Direction Pulleys: These redirect the rope from the ground up and over structural members, preventing edge contact and rope abrasion.

-

Redundancy: The main and belay systems are anchored independently. A Figure 8 loop and pre-rigged carabiners allow easy connection to secure, bombproof anchor points.

With both systems in place, the subject is disconnected from any fall restraint, and the lowering system takes over. Every rope path is checked for obstructions and sharp edges before descent begins.

Phase 3: Controlled Lowering – Moving Through Vertical Complexity

Lowering a subject from extreme heights requires patience and a solid plan. Sometimes, the rope length isn’t enough. That’s where knot-passing and mid-descent adjustments come in.

Common Obstacles in Lowering:

-

Knot Passing at Height: When ropes are too short, knots must pass through pulleys mid-lowering—a simple act on flat ground becomes far more difficult 200 feet up. A second rescuer may be positioned to assist at that point.

-

Structural Interference: Rescue loads must be guided around antenna brackets, ladder rungs, or cable junctions. Skate blocks and taglines can help redirect movement.

-

Multi-Pitch Complexity: In some rescues, additional systems are staged on intermediate levels to control the descent or receive the patient partway down.

When operating from a high platform like a tower crane, teams must weigh the efficiency of building systems at height versus rigging everything from the ground. Each approach comes with trade-offs in time, complexity, and safety.

Fall Arrest Rescue – When the Subject Is Already Hanging

If the subject is suspended in a fall arrest system:

-

Direct Connection: Rescuers attach to the dorsal connection point on the subject’s harness.

-

Load Transfer: A slight lift (using a piggyback raise or vector pull) removes tension from the subject’s lanyard, allowing safe disconnection.

-

Controlled Cut (if needed): In rare utility or tactical situations, rescuers may cut a jammed or damaged pole strap once the subject is safely supported.

The Rescue Standard Is Higher—Literally

Tower and ladder rescues demand a different mindset. They aren’t just high-angle—they’re high-stakes. It’s not just about gear or technique. It’s about layers of preparation, precise communication, and an unbroken chain of trust between team members.

The rescue community cannot approach these missions casually. These are rescues where knot passing must be seamless, edges must be anticipated, and subject condition must be factored into every pulley placement. For these reasons, training must mirror reality. Relying on rehearsed gym drills won’t cut it.

When the call comes, high-angle heroes don’t hope they’re ready. They’ve trained for this—and every step upward confirms it.

Peace on your Days

Lance