Directional Frame Setup and Guying Angles in Rescue Rigging

When deploying directional frames in rope rescue, especially A-frame or gin pole setups, small adjustments in angles can make the difference between a reliable system and one on the edge of collapse. Proper guying—both front and back—is not just about holding the frame upright. It’s about resisting unexpected forces that weren’t part of the plan.

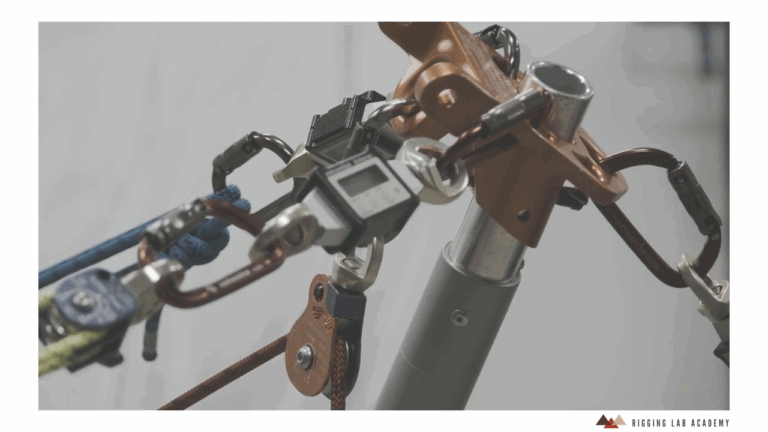

In this scenario, a loaded directional frame is holding 100 kilograms, stabilized by 16 kilograms of restraining force. Visually, the frame resembles a classic A-frame with two guying systems—front and back—anchored in opposition to the applied load. On paper, it works. But real-world rigging rarely stays on paper.

Evaluating the Applied Force and Guying Angles

The first step in validating a directional frame is checking the applied force angle. In this case, the load is almost perfectly aligned with the plane of the frame, deviating less than five degrees. That’s excellent—it minimizes side loading and keeps the structure acting predictably.

The front guy angle also supports this design, resisting movement with minimal deviation from ideal alignment.

-

Applied force angle: < 5 degrees off the frame plane

-

Front guy angle: Wider than applied force angle (pass)

-

Back guy angle (initially): Too shallow, only ~10 degrees

-

Corrected back guy: Extended to 45–50 degrees for stability

With the rear guy repositioned to a proper anchor point, the system balances beautifully. The angle between the frame plane and the front guy remains around 35 degrees, while the rear guy now opposes forces at a favorable 45–50 degrees.

Why the Back Guy Angle Matters

A directional frame isn’t only about load direction—it’s about what happens if the unexpected occurs. If someone slips and instinctively grabs the frame, or if a fall-arrest lanyard gets clipped to the top member, a sudden off-axis load could occur. That’s when poor back guying can become catastrophic.

The back guy does more than just hold shape—it prevents system failure when the load shifts or becomes dynamic. That’s why it must oppose the worst-case force, not just the intended one.

Rules for a Directional Frame Setup That Holds

To meet the safety and structural expectations of a field-resilient frame, three key rules must be satisfied:

-

Applied force angle must be less than the opposing guy angle.

-

Guy lines should be as wide and symmetrical as the environment allows.

-

Back guys must be planned not just for static load, but for accidental dynamic loading as well.

In this build:

-

The applied load is resisted cleanly by front and back guys.

-

Load distribution is known—30 kg on the front guy, 40 kg on the back.

-

The frame stays planted with minimal correction needed during setup.

Beyond Stability—Planning for the Unplanned

This setup doesn’t just hold under expected conditions. It’s built to withstand misuse, missteps, and moments of chaos. If someone grabs the frame in panic or clips in where they shouldn’t, the system has enough structural integrity to absorb the shock without tipping or folding.

This is the difference between building for stability and rigging for resilience.

Conclusion

When building a directional frame setup, especially with a gin pole or A-frame, success depends on getting your guy angles and force vectors right—and planning for what you don’t expect. By keeping applied force within five degrees of the frame plane, widening guy angles, and repositioning rear anchors, your system is ready for more than ideal loads.

It’s ready for the real world.

Peace on your Days

Lance