Anchor systems are the backbone of rope rescue. Every lift, lower, redirect, tension system, or directional frame is supported—literally—by the quality of the anchors that carry the load. The most skilled team and the most capable hardware cannot compensate for anchors that are poorly selected, misaligned with the load, or misunderstood. When anchors are engineered correctly, the entire rescue system becomes predictable. When they are improvised without understanding, the system carries hidden risk. Everything begins with anchor fundamentals, expands into force dynamics, moves through configuration types, and ultimately supports real-world rigging applications.

Professional rigging treats anchors as engineered structures, not as clip-in points. The process involves evaluating anchor integrity, understanding the forces that will act on them, and ensuring the configuration matches the operational demands. The principles that govern anchors also govern every piece of rigging downstream. The clearer the anchor logic, the stronger the entire system becomes.

Anchor Fundamentals & Evaluation

Evaluating an anchor begins with the understanding that a life will depend on its behavior. Strength alone is not enough; the anchor must be predictable, stable, and aligned with the direction of pull. Rescue anchors must be selected not only for their inherent capability but for how they perform as part of a full system. A sound anchor is one that stays sound under load, under movement, and under the combined forces created by the entire rigging system.

The ERNEST framework—Equalized, Redundant, No Extension, Effective, Solid, Timely—remains one of the clearest lenses for anchor evaluation. Each component points to a failure mode that must be eliminated. Load must stay distributed. A single failure cannot collapse the system. The loss of one component must not generate a shock load. The system should perform its purpose without unnecessary complexity. Anchor elements must be truly solid. And the system must be buildable within the time constraints of the rescue. ERNEST is not decoration; it is the logic that prevents catastrophic surprises.

Single point anchors are ideal because they eliminate variables. When a single element has unquestionable strength and alignment, the rigger gains simplicity, clarity, and predictability. Structural steel, engineered eyebolts, large live trees, and industrial anchors fall into this category. These anchors must be inspected critically for hidden weaknesses and must carry the load through their strongest axis. If the anchor cannot meet that standard, it is not a single point—no matter how convenient it appears.

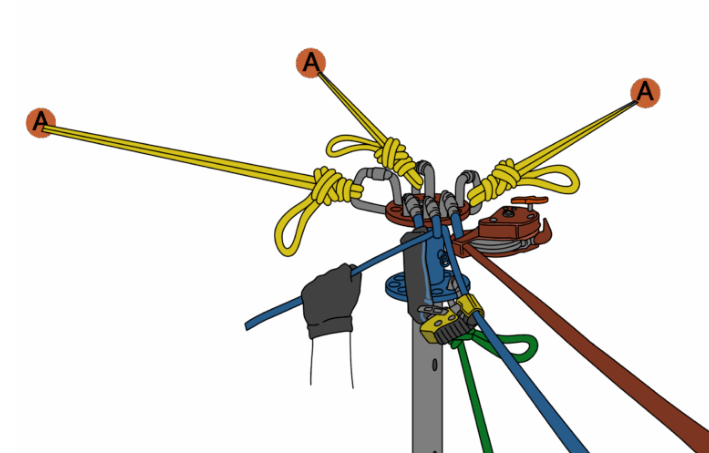

Multi-point anchors become the solution when the environment does not offer a truly reliable single element. In this case, several anchor points are combined with intentional engineering. Load-sharing must be real, not symbolic. The legs must be tensioned correctly. The angles must be controlled. Redundancy must be meaningful. A multi-point anchor is not safer by default; it is only safer when the system is built with disciplined logic.

Rescue anchors fall into several common categories—natural, structural, artificial protection, and vehicle-based. Each category brings its own considerations. Natural anchors require understanding of root systems, soil stability, and tree health. Structural anchors require evaluation of design intent and load rating. Artificial protection demands correct placement and alignment. Vehicle anchors require control over movement and loading direction. Regardless of category, the evaluation standard does not change: the anchor must be unquestionably compatible with the anticipated forces.

-

ERNEST clarifies both anchor selection and anchor behavior.

-

Single points are preferable when truly capable of supporting system loads.

-

Multi-point anchors must be engineered, not assumed.

-

Anchor categories determine inspection criteria and failure considerations.

Force Dynamics & Vector Management

Understanding anchor systems means understanding force. Rescue rigging is an application of vector physics, not merely rope handling. Every rope under tension creates a directional force, and every change in rope direction creates a new vector that must be resolved. The anchor is where those forces converge. If the anchor is not aligned to accept them, it will behave unpredictably.

The concept of the resultant force is central. Any time two legs of rope meet at an angle—whether in a multi-point anchor, a directional, or an AHD—those legs create a combined force at the master point. That resultant acts in a specific direction. If that direction is not supported by the anchor, the system becomes unstable. When the angle between anchor legs increases, the force on each leg increases disproportionately. Many anchors fail not because the element is weak but because the rigger unintentionally creates excessive angle forces.

Mechanical advantage complicates this picture. A 3:1 haul system reduces the effort required to lift a load but increases the force returned to the anchor. Friction may limit this somewhat, but the general rule remains: increasing mechanical advantage increases anchor load. Complex or stacked systems can multiply forces beyond what rescuers intuitively expect. Twin tension systems create two high-load paths that both require fully capable anchors.

Shock loading is another critical part of force dynamics. Systems rarely fail under slow, steady load. They fail when slack allows sudden movement. Extension in an anchor leg, loss of a multi-point component, abrupt descent control, or a snagged litter transitioning to free movement can generate a force spike many times higher than the static load. Managing shock loading requires minimizing slack, eliminating extension, and ensuring operators maintain smooth transitions during movement.

The rescuer who understands vectors does not rig reactively. They rig with intention, shaping force paths deliberately and keeping angles, tension, and direction under control.

-

Vector forces set the real load on anchor legs—not the weight of the subject.

-

Wide anchor angles amplify force to dangerous levels.

-

Mechanical advantage increases anchor load even as it reduces rescuer effort.

-

Shock loads exceed static forces and must be eliminated through design.

Anchor Configuration Types

Anchor configuration determines how anchor elements work together and how the load is ultimately supported. This is where anchor evaluation and force dynamics become practical rigging.

Equalized anchors are used when the load must be shared across multiple points. Their success depends on controlled angles, appropriate leg tensioning, and clear alignment of the resultant. Equalization is not a guarantee; it is a goal that must be achieved through tight rigging discipline. Poorly executed equalization simply creates unpredictable loading.

Knots function as the structural joints of anchor systems. The type of knot, the direction it faces, the way it is dressed, and how it handles load determines the clarity and reliability of the system. Figure eight variants, clove hitches, bunny ears, bowline derivatives, tensioning knots, and mid-line loops all play specific roles. A knot is not merely a connector—it shapes load flow.

Advanced anchors provide adjustability for changing load direction or operational demands. These include adjustable directionals, variable-length anchor legs, and tension-managed structures that allow the master point to be refined. However, adjustability must not come at the cost of system readability. If the system becomes visually confusing, it becomes operationally unsafe.

Reinforcement and directional control allow the rigger to place the resultant exactly where it belongs. Back-ties stabilize weak structural anchors. Deviations shift rope paths away from edges. Directionals and AHDs reposition the load relative to anchor footprint. Good rigging is often the art of controlling direction, not just holding weight.

-

Equalized anchors require precise angle control and leg tensioning.

-

Knots define structure, load path, and clarity of the anchor system.

-

Adjustable anchors must remain easy to inspect.

-

Directional control determines where the resultant truly lands.

Rigging Applications & Techniques

Rigging applications are where anchors stop being theoretical and start carrying real operational load. These systems—artificial high directionals, horizontal systems, specialized movement techniques—push anchor logic into complex, high-demand environments.

Artificial high directionals (AHDs) create a high point where none exists. They use structural engineering to reposition the rope above an edge, steer the resultant into a controlled footprint, and reduce friction and edge hazard. AHDs concentrate force at their head and at their feet. This requires precise anchor integration—guying, back-tying, and maintaining the AHD within its safe operating cone. Misaligned AHD anchors create leverage risks that magnify load rapidly.

Horizontal systems introduce some of the most challenging forces in rescue rigging. A guiding line offsets the load from a structure; a skate block combines vertical descent with lateral travel; a trackline carries tension that increases as sag decreases; and a full highline demands industrial-strength anchor design. These systems behave differently than vertical lowers. They apply combinations of vertical and lateral vectors, increasing force at the anchors even when overall system tension seems modest. Horizontal systems require absolute clarity in anchor strength, angle management, and operator control. Abrupt movement spikes force. Smooth control preserves anchor integrity.

Specialized techniques such as twin tension systems, mirrored hauls, diagonal offsets, and confined space rigging place complex demands on anchors because load paths change during operation. Anchors in these systems must be designed for multiple directions of pull, potential reversals, and dynamic movement. Predictability becomes the primary design goal.

-

AHDs focus force into specific points requiring disciplined anchor tying.

-

Horizontal systems blend vertical and horizontal vectors, raising anchor loads.

-

Smooth descent control directly affects force magnitude.

-

Specialized systems must anticipate multiple vectors and transitions.

Conclusion

Anchor systems and rigging principles are not separate disciplines; they are a single integrated framework for creating predictable outcomes under load. Evaluating anchors with rigor, understanding the forces that act on them, configuring them with clarity, and applying them to complex rescue environments all contribute to a system that behaves the way rescuers intend. Successful rescue rigging is the expression of predictable anchor behavior. When anchors are designed with deep understanding of fundamentals, vectors, and configuration logic, every other part of the system becomes safer, smoother, and more controllable.