The Immutable Laws of Rigging: A Guide to First Principles

This document outlines five principles of rescue rigging—foundational truths that are non-negotiable and from which all safe practice is derived. These principles cannot be reduced further; they are the absolute realities that govern every decision made in a life-or-death scenario.

1. The Principle of Inherent Fallibility

Scenario: A rescue team is setting a main anchor off a seemingly solid, large boulder. They use a single, strong rescue rope, confident in its breaking strength and the stability of the boulder. During the lowering operation, the boulder shifts slightly, revealing a deep, unseen crack that causes it to fracture. The single rope snaps, and the rescuer and victim fall.

Defense: This proves that even a perceived “solid” anchor is not a guarantee. The principle of Inherent Fallibility dictates that everything—even the ground itself—has an unseen weakness. You cannot deduce this weakness from a visual inspection. Therefore, the only logical, non-reducible practice is to build redundancy. The failure was not due to poor judgment; it was due to the absolute, undeniable fact that everything can and will fail under some condition. The system failed because it violated the principle by not assuming this fallibility from the start.

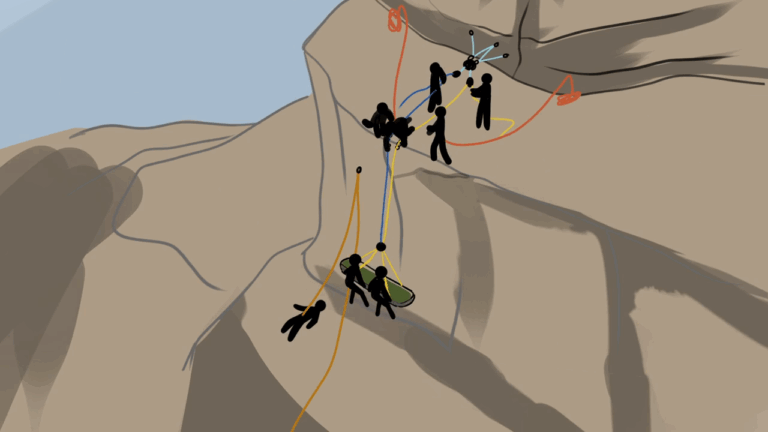

2. The Principle of Collective Failure

Scenario: A team rigs a three-point anchor system, with each anchor rated to hold more than the anticipated load. Two of the anchors are rigged correctly, but the third uses a knot that is not cinched tight. As the load is applied, the system shifts. The loose knot slips, but instead of simply failing, the slip causes a sharp, focused load onto one of the other, still-intact anchor points, causing it to fail. The entire system then collapses.

Defense: This scenario proves that a system is not stronger than the sum of its parts. The system didn’t fail at a single weak point; the weakness in one part (the uncinched knot) directly caused the failure of a seemingly strong part. This demonstrates that all elements are interconnected, and a fault in one creates a domino effect. The principle of Collective Failure is an absolute truth—you cannot separate the components’ performance from the system’s performance. The entire chain, including the human element, is only as strong as its weakest link.

3. The Principle of Dynamic Shock

Scenario: A rescuer on a rope is being lowered to a victim. The rope runs over a sharp edge, but the rescuer has placed a simple edge pad. The rescuer’s movement is smooth. Suddenly, a piece of loose rock falls from above and hits the rope, causing a momentary jolt. The edge pad shifts and the rope instantly severs over the sharp edge, as the force of the jolt far exceeds its working capacity.

Defense: The static weight of the rescuer was well within the rope’s limit. The rope failed not because the load was too heavy, but because a momentary, unexpected event introduced a dynamic shock. This shock load, even if it lasts for only a millisecond, generates a force that is orders of magnitude higher than a static load. This is a fundamental law of physics. The principle of Dynamic Shock is non-reducible—you can’t “reduce” a shock load to a simple weight calculation. It is a separate and distinct phenomenon that must be designed for, proving its status as a first principle.

4. The Principle of Ultimate Simplicity

Scenario: A rescue team sets up an overly complex mechanical advantage system to haul a victim. The system uses a series of pulleys, prusik knots, and multiple points of direction change. In the middle of the haul, the lead rescuer yells a command, but in the confusion, a team member on a less critical part of the system releases a knot too early, thinking it was for them. This creates a tangle, halting the operation.

Defense: The system was mechanically sound. The failure was a direct result of the system’s complexity. The Principle of Ultimate Simplicity is a first principle of human factors engineering. When you add more steps, more knots, and more decision points, you increase the cognitive load on the team. This, in turn, creates an exponential increase in the potential for human error. You can’t train away this principle; it’s a constant. The simplest system is not just easier, it is fundamentally safer because it reduces the number of points at which human fallibility can introduce a catastrophic failure.

5. The Principle of Unconditional Non-Extension

Scenario: Two rescuers are on a belay, attached to a two-point anchor. The system is rigged with an equalized but “extending” setup—meaning if one anchor fails, the other can move significantly before the load is transferred. One of the anchors fails. The other anchor holds, but the movement of the rope and the sudden shock causes the rescuer to lose their grip on the brake hand. The rescuer does not fall, but the loss of control puts the entire system in jeopardy.

Defense: The system, by design, allowed for movement, which led to a loss of control. The principle of Unconditional Non-Extension is a fundamental law of motion in a rescue system. Any extension creates a potential for a shock load and, critically, a loss of control. The very act of movement can create a secondary failure. This principle is not a “good idea”; it’s a necessity. You can’t have a system that “moves a little” and expect it to be safe, as that movement can have unpredictable and dangerous consequences that are not reducible to simple force calculations.